The Uffizi Gallery Museum in Florence

Around the middle of the 16th century, Cosimo I de' Medici decided to construct a building that would unite the public offices of the Grand Duchy in a single complex.

Even after the building was converted into a museum, the name “Ufizi” (office) remained on the building. In 1559, the building project was entrusted to Giorgio Vasari, painter, art historian and one of the best architects and town planners of the time.

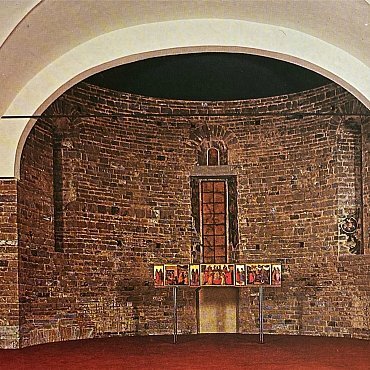

Large plots of land could be acquired by purchasing all the houses between Piazza della Signoria and the Arno River. The complex also included the ancient church of San Piero Schiraggio, the remains of which still stand in the area today.

There are apses outside, on the Via della Ninna side and inside the building.

By 1565 the factory was nearly completed, to the point that the long Vasarian “corridor” that, crossing the Arno on the Ponte Vecchio, joins the Uffizi to the Pitti Palace, and the aerial passageway that, bypassing Via della Ninna, leads into the Palazzo Vecchio, had already been built.

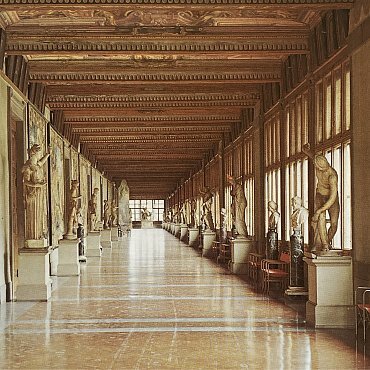

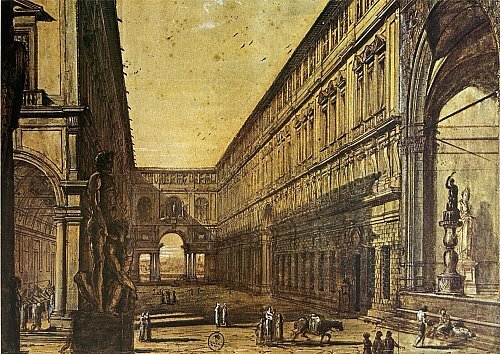

Vasari's construction consists of three wings enclosing a large square with three rows of porticoes.

The portico opens onto the Arno with a magnificent and scenic archway at the rear. The architecture of the building is inspired by the traditional combination of white plaster and the alternation of light and dark, full and empty, and the gray of the pietra serena. In the Uffizi building, Vasari mainly applied Michelangelo's modules found in the Laurentian Library room, designed by Buonarroti in 1524.

Indeed, this model is clearly echoed in the long forecourt that, on the outside, reproduces the system of pietra serena stone members devised by Michelangelo for the Laurentian Library. By inserting the Uffizi complex, in a new and fully 16th-century style, into the medieval context of the Florentine historic center, Vasari was also concerned not to disturb the city's harmonious urban fabric dating back to the 13th century, seeking above all to create a marvelous scenic opening for the massive bulk of the Palazzo Vecchio.

Cosimo's successor, Francesco I, a keen student of science and the arts, decided to renovate the loggia that crowned the building in order to allocate some rooms for his collections of art objects, weapons, scientific curiosities and laboratories.

In 1580 the work was entrusted to Bernardo Buontalenti, who simultaneously began the construction of the Grand Ducal Theater on the second floor (where the Cabinet of Drawings and Prints is now located) and the Tribuna on the second floor, intended to house the best pieces of the Medici collection.

By 1586 the entire transformation was nearly complete. Soon, all the works that were distributed between Palazzo Vecchio and Palazzo Medici, belonging to Cosimo the Elder, Lorenzo the Magnificent, and Francesco's father Cosimo I, were grouped together in the new rooms.

To the first nucleus of works, which already included masterpieces by Sandro Botticelli, Paolo Uccello, and Filippo Lippi, other paintings and sculptures were added over the centuries, thanks to the passionate interest of Francesco I's successors. Ferdinand I had all the works he had collected in Rome at the Villa Medici transferred to the Uffizi.

Explore the Uffizi Gallery Museum

Ferdinand II, in 1631, placed there a very important group of paintings including works by Piero della Francesca, Titian and Raphael, works that had been bequeathed to his wife Vittoria della Rovere by the dukes of Urbino.

In 1675 the Uffizi was enriched by the collection of Cardinal Leopold de' Medici, which included some portraits and the first nucleus of the collection of drawings. Cosimo III collected gems, medals and coins and brought from Rome the famous Venus later called “dei Medici,” the Arrotino, the Lottatori and other notable antique sculptures.

Anna Maria Lodovica, Electrice Palatina and the last Medici heiress, who had already enlarged the valuable collection with Flemish and German paintings, made a gift of the entire collection to the Tuscan State in her will (1743), on the condition that all the works remain in Florence.

The Lorraines, continuing the Medici tradition, also contributed to increasing the artistic patrimony of the gallery: Francesco donated ancient sculptures and coins, while Pietro Leopoldo, in addition to reuniting the Medici-owned works still dispersed between Florence and Rome, had the Niobe and Niobidi group, for which he had a special room built in 1780, transported from the Villa Medici in Rome.

Peter Leopold is also credited with initiating a reorganization of the gallery according to modern museographic criteria and opening it to the public. In the 19th century, when a number of specialized museums were created in Florence (the Archaeological Museum, the Bargello National Museum, the San Marco Museum, etc.), the Uffizi lost part of its collections.

Part of the building was designated to house the State Archives in 1852, and at the end of the century, the theater was destroyed to make way for more rooms. Toward the middle of the 19th century, the building's exterior underwent some transformations: niches were opened in the columns of the portico on the square, and statues depicting illustrious Tuscans were placed there, executed by sculptors of the time such as Giovanni Dupré and Lorenzo Bartolini.

As for the present, two important initiatives are worth mentioning: the recent reopening of the Vasarian Corridor, in which works from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries have been arranged along with the remarkable collection of self-portraits, and the creation of an educational section intended primarily for the organization of study programs and guided tours for students.